You don’t need to pick up exactly where you left off. Use these tips to reflect on how you want your life to look.

BY BETHANY TEACHMAN | JULY 15, 2021

You’ve been waiting…and waiting…and waiting for this amazing, magical day when you could return to “normal life.”

For many people in the U.S., it feels like that dim light at the end of the pandemic tunnel is becoming brighter. My 12- and 14-year-old daughters now have their first shot, with the second one soon to follow. I was euphoric when the kids received their vaccinations, choking up under my mask at the relief that my family was now unlikely to get sick or pass the coronavirus on to others more vulnerable than we are. Finally our family could start returning to so-called normal life.

But what should those of us fortunate enough to be vaccinated return to? I didn’t exactly feel euphoric each day in my normal life pre-COVID-19. How should you choose what to rebuild, what to leave behind, and what new paths to try for the first time? Clinical psychological science provides some helpful clues for how to chart your course out of pandemic life.

1. Set realistic expectations

You are less likely to be disappointed if you set reasonable expectations.

For instance, you’ll likely feel some anxiety as you try to figure out what’s OK to do and what’s still risky. Even as the risk level has declined in many places, there is still uncertainty and unpredictability tied to the current coronavirus risks, and it’s natural to feel anxious or ambivalent when letting go of an established habit, like wearing masks. So, be ready for some anxiety and realize it doesn’t mean something is wrong—it’s a natural reaction to a very unnatural situation.

It’s also likely that many social interactions will feel a little awkward at first. Most Americans are out of practice socializing, and repeated practice is what helps us feel comfortable.

Even if your social skills were at their peak, the current moment serves up a lot to navigate interpersonally. Chances are you won’t always agree with the people in your life on where to draw the lines about what’s safe and what’s not. There are going to be some complicated summer parties to navigate given many families have some members vaccinated and some not. That will be frustrating after waiting so long to finally get together.

And you won’t automatically have warm, fuzzy feelings about all your colleagues, family, friends, and neighbors. Many of those little annoyances that cropped up in your interactions before you ever heard of COVID-19 will still be there.

So, expect some awkwardness, frustration, and annoyance—everyone’s creating new patterns and adjusting to changed relationships. This should all get easier with time and practice, but having realistic expectations can make the transition smoother.

2. Live your values

To help plan which activities and relationships to put time into, think about your priorities.

Living in ways that are consistent with your values can promote well-being and reduce anxiety and depression. Many therapeutic exercises are designed to help reduce the discrepancy between your stated values and the choices you make day to day.

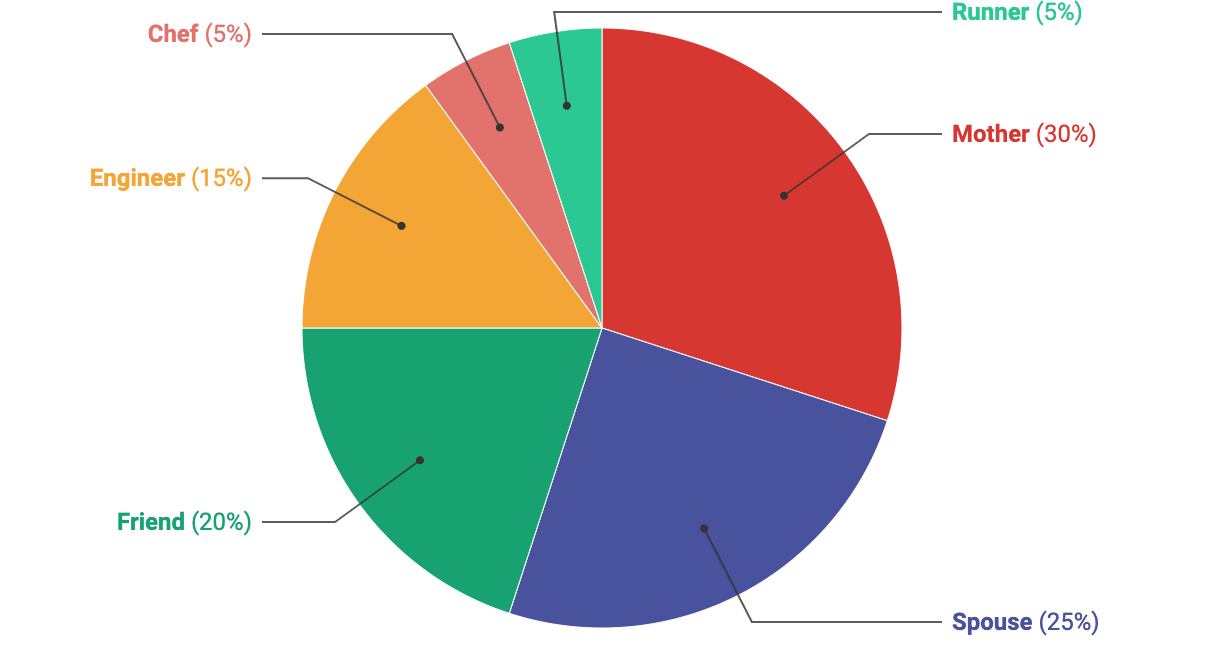

Imagine you are asked to carve a pie to illustrate your different roles and how important each is to the way you feel about yourself and the values you prioritize. You might value your roles as a mother, a spouse, and a friend most highly, assigning them the biggest pieces of your pie.

What she values most about herself. Thinking about your priorities is the first step toward figuring out how closely your real life aligns with them.

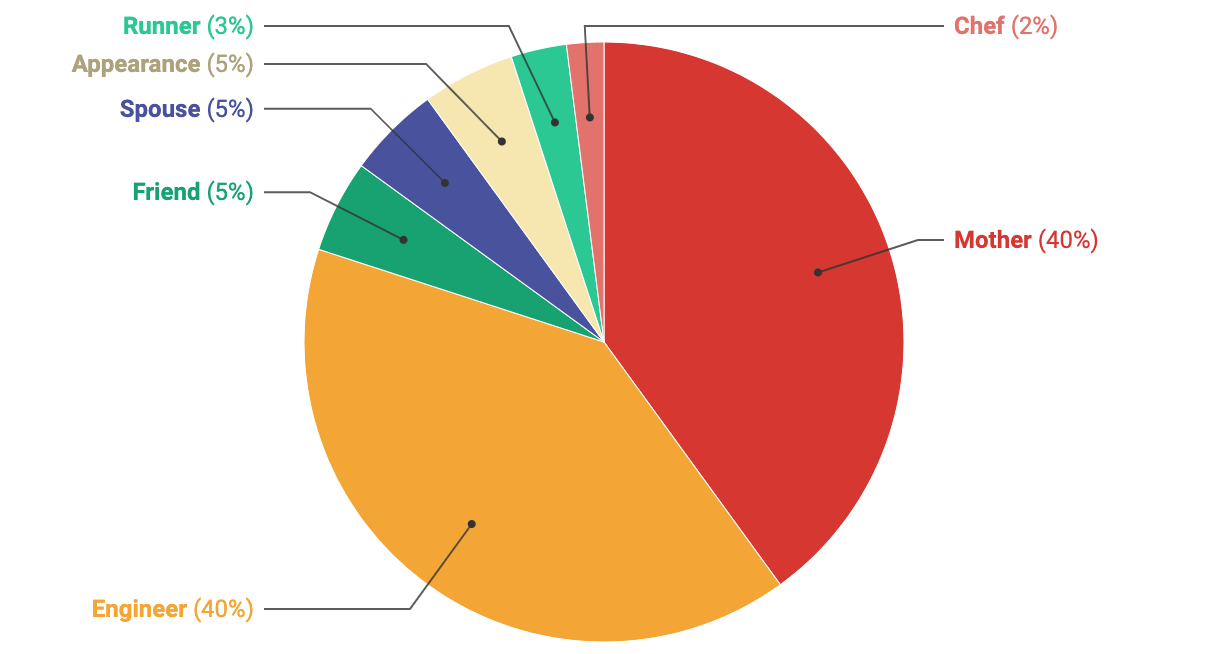

Now, what if you were asked to carve that pie in a way that reflects how you actually allocate your time and energy, or how you actually tend to evaluate yourself. Is the time you spend with friends much lower than its value to you? Is the tendency to judge yourself based on rigid work demands much higher?

How she really spends her time. Recognizing that your real-life choices don’t match up with what you value the most can help you identify the parts of your life that deserve a higher priority.

Of course, time is not the only meaningful metric, and all of us have periods when certain parts of our lives need to dominate—think about life as a parent of a newborn, or a student during final exams. But this process of considering your values and trying to align what you value and how you live can help guide your choices during this complex time.

3. Keep track

Clinical psychologists recommend engaging in activities that feel rewarding in some way to stave off negative moods. Doing things that are pleasurable, that provide a sense of accomplishment or help you meet your goals, can all feel rewarding, so this isn’t just about having fun.

For most people, some balance of fun, productive, social, active, and relaxing activities in life is key to feeling like your different needs are being met. So, try keeping track of your activities and mood for a week. See when you feel more or less happy and when you feel like you’re meeting your goals, and adjust accordingly. It will take some trial and error to find the balance of activities that provides that sense of reward.

4. Is this a time of growth or preservation?

There is fascinating research showing that the perception of time can influence your goals and motivation. If you feel time is waning—as often occurs for older adults or those experiencing a serious illness—you are likely to seek deeper connections with a smaller number of people. Alternatively, those who feel time is open-ended and expansive tend to seek new relationships and experiences.

As restrictions loosen, are you desperate to visit a close friend in the town you grew up in? Or more excited to travel to an exotic location and make new friends? There isn’t a right answer, but this research can help you consider your current priorities and plan that next reunion or trip accordingly.

5. Recognize your privilege and pay it forward

If you are vaccinated and healthy and can return to more normal activities, then you are in a fortunate group after a year of such devastating losses. As you plan how to use this time, consider the research showing that your emotional health improves when you do things to benefit others.

Being intentional about helping others is a win-win. Many people and communities are in need right now, so think about how you can contribute—be it time, money, resources, skills, or a listening ear. Asking what your community needs to recover and thrive and how you can help address those needs, as well as considering what you and your household need, can boost everyone’s well-being.

As the return to so-called normal life becomes more of a reality, don’t idealize post-pandemic life or you are bound to be disappointed. Instead, be grateful and intentional about what you choose to do with this gift of a reboot. With a little thought, you can do better than “normal